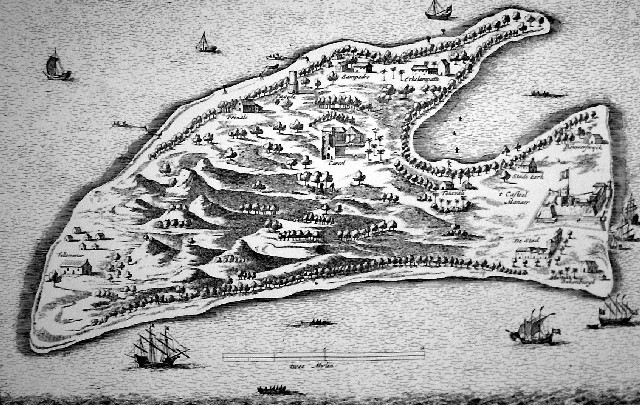

Northern Ceylon: starving Jaffanapatnam

Van Goens, the “commissioner, admiral and commander-in-the-field of the Western Quarters”, arrived in Colombo from the Goa blockade on the 1st of January 1658. As explained in the last chapter, the entire west coast of Ceylon had by now been conquered on the Portuguese. The east coast at this time remained free of European power: here were the harbours of the Raja Singha, king of the Kandy Kingdom. On the north of the island, however, the Portuguese were still in control of Jaffanapatnam and Mannar. Van Goens was here to change that, and to execute his own plans of sweeping the Portuguese entirely out of India and Ceylon.

Whereas Van Goens had left Goa with a fighting force of 800, several of his ships had gone missing and he had arrived before Colombo bringing only 450 soldiers. In order to be able to undertake something against the Portuguese positions in the north, he would therefore need to draw a substantial number of soldiers from the Ceylonese garrisons.[1] The Ceylonese governor Van der Meijden, however, was loath to spare any troops, as he feared an attack from inland Ceylon. Whereas originally the Raja Singha had worked together with the Company to oust the Portuguese, he had soon realised that by aiding the Company against the Portuguese he was just replacing one obnoxious European power with another, and in the past decade relations had steadily worsened. By now, the disposition of the Raja Singha towards the voc had become whimsical at best, and Van der Meijden was anxious that the king might join the Portuguese in an attempt at reconquering the Dutch settlements. Seeing his garrisons march off to war was therefore not an attractive prospect to the governor.[2]

Map of Southern India and Nothern Ceylon, with the route of Van Goens campaign schematically drawn in by me.

In the council meeting of the 7th of January, Van Goens however managed to overrule Van der Meijden, and the council finally decided that the 450 soldiers brought from Goa would be supplemented with another 800 European soldiers as well as 300 Lascars from the Ceylonese garrisons. It was now decided to first move against the island of Mannar with the entire force. From there, the army would subsequently move against Jaffanapatnam on the mainland.[3]

Circumstances, however, threw the planning upside down before the army could even move north. On the 16th of January, Van Goens received word that the Naarden, one of the missing ships of his original fleet, had been found. Its commander, Van der Laan, had felt confident enough to move against the unfortified Portuguese city of Tuticorin on the Coromandel Coast on his own initiative. He had subsequently failed to land and take the city, but with his ship currently had several Portuguese frigates pinned down in the bay there.

Van Goens was thus obliged to first mop up what Van der Laan had started. As Tuticorin was an unfortified city, and Van Goens now had quite an army assembled, this should hardly cause any delay in conquering the remaining Portuguese strongholds on Ceylon. On the 18th of January he sent out four yachts, bringing 146 soldiers, to Tuticorin, to help the Naarden seal in the Portuguese ships; the next day, he was able to send out another three small yachts. His own ship, the Goes, was ready to depart for Tuticorin on the 21st of January.

Arriving before Tuticorin three days later, Van Goens found that, including his ship, twelve voc vessels were now before the city, with a total fighting force of 800 men. That same night, the troops were brought onto the small ships, and landed near the city. The next morning Tuticorin was taken practically without a fight. The open city had only 80 Portuguese soldiers defending it. As soon as the voc fleet had taken out the three Portuguese frigates defending the city, the Portuguese force had simply fled.

Taking the city might have been easy; a more complex question was what to do with it afterwards. In a council meeting on the 28th of January, the idea of building and garrisoning a small fortification was rejected; this would merely drain the available fighting force, and the voc had no interest in Tuticorin, either strategically or with regard to trade. It was therefore decided to send a representative, Jacob van Rhee, to the Nayak of Madura, ruler of the region. Van Rhee was simply to give the city over to him, on the condition that no Portuguese would be allowed back in. Thus, the Company hoped to have driven the Portuguese out, without the burden of having to guard the door themselves afterwards.[4]

Having put things in order at Tuticorin, the fleet was ready to continue to Mannar. Missions to the local rulers had meanwhile yielded support to the Company attack on the Portuguese, in the form of small ships suitable for landing, and even warriors. While some ships of the fleet were already ahead, Van Goens was now waiting for these reinforcements, much to his discontent. He felt that his army was strong enough to move against Mannar without these warriors, and he would rather have the advantage of having a full moon during the attack. Just as Van Goens was preparing to depart without the promised reinforcements on the 11th of February, the small ships finally arrived. Van Goens then met up with the other ships at the island of Rammanacoylam (present-day Rameswaran, the westernmost island of Rama’s Bridge.) The island of Mannar lay just on the other side of the Strait.

Due to adverse winds, the fleet only arrived before the southcoast of Mannar on the 19th of February, finding that the Portuguese had apparently been aware of the Company’s plans. The southern coast was fortified by a trench two miles long, and eight frigates were defending the coastline. As it later turned out, the Portuguese had assembled 700 soldiers for the defence of the island. Landing the Company force on a different part of the island was undesirable: the northwest coast was also well-defended, and the east coast was covered by a fortification on the Ceylonese mainland just across. The troops then, would just have to land on the south coast, as had been planned, but not before the Portuguese ships, the biggest threat to a landing of the army, had been destroyed or taken.

The attack on the Portuguese ships began the next day. Destroying the Portuguese ships, however, proved harder than expected: by the second day of the naval battle, the Company fleet had only destroyed one Portuguese ship, at the cost of several lives on Company side. It was then decided to try and force the landing by a somewhat unusual manoeuvre. In the evening of the 21st, the voc fleet first pretended to move away from the island, but during the night it returned, and manoeuvred the smaller ships of the fleet right in between the Portuguese ships and the beach, within musket range of the Portuguese soldiers in the trench. The Portuguese subsequently daringly copied this manoeuvre, sailing their frigates right in between the coast and the Company ships to prevent a landing. This was extremely precarious as the Dutch ships were already so close to the beach that they were in danger of stranding. This action turned out to be the end of the Portuguese frigates: the Company convincingly won the close combat which followed, destroying virtually all the Portuguese vessels. The landing could now proceed.

The naval battle of the past three days turned out to have been the most difficult part of conquering the island: in the morning of the 22nd, the Company troops landed, and by the next morning the island was practically in the hands of the Company. At least 400 of the 700 Portuguese soldiers had fled across the water and were now making for Jaffanapatnam. For now, this was obviously advantageous to the Company, as the various Portuguese fortifications were taken with hardly a fight. The disadvantage was, however, that these soldiers would now still have to be defeated at Jaffanapatnam, and that the Portuguese there would start preparing their defences as soon as the soldiers would bring the news of the fall of Mannar.

Van Goens therefore decided to immediately pursue the fleeing Portuguese army, leaving only 60 soldiers on Mannar. On the 25th of February, the bulk of the army crossed to the Ceylonese mainland near Matotte. The march which was supposed to overtake the Portuguese army or at least arrive at Jaffanapatnam shortly after the Portuguese force, only proceeded slowly, due to disease and a lack of supplies among the soldiers. As Baldaeus, a preacher and missionary who was marching along with the army, describes: “[A]s we had no great plenty of provisions, we allowed only a small provision of rice every day to each soldier, rather than incommode the inhabitants: and finding our forces extremely tired by the long marches, and consequently incapable of engaging with the same advantage with the enemy in case they should be attacked, it was resolved instead of marching up to the head of the river through the sandy ground, to pass the river in boats [...]”[5]

The latter part of Baldaeus’ description of the march requires some explanation. The city of Jaffanapatnam was on a peninsula going by the same name, only connected to the Ceylonese mainland by a small landbridge on the eastside. The Company army, however, had marched due north, taking the shortest route. This meant that they had to cross the bay (this long and narrow bay was often called the ‘salty river’, and this is what Baldaeus refers to), which rendered the army vulnerable. When the army arrived before the water after a three days’ march, the Portuguese, however, were nowhere to be seen. Although crossing the bay finally took 24 hours, there was no Portuguese attempt to prevent it. Baldaeus tells how the Portuguese had supposed that the Company army was taking the long way around over the land bridge. The Portuguese had therefore moved away from the other side of the water the day before. Apparently the earlier delays of the march had at least been good for something.

The Company army arrived before Jaffanapatnam on the 7th of March, and split up in two forces. Van Goens circumvented the fortress and moved part of the force to the north of the city, Van der Laan attacked from the south. Jaffanapatnam, unlike many other Portuguese cities in Asia, was not walled all around, but had a citadel on the coast, around which the city was built. Van Goens easily took the northern part of the city, which was the smallest and housed fewer strong buildings. Van der Laan, however, had to wage a true city guerrilla on the south side: the Portuguese had barricaded the streets, and were firing from strongly built churches and stone houses. Van der Laan had to use heavy cannon to bring these down and advance. In order to aid in the conquest of the southside of the city, Van Goens came back from the northside with his troops. The efforts there were further helped along by the arrival of the Salamander from Mannar, bringing 209 soldiers. These soldiers had come from the Mars, another ship that had gone missing from Van Goens’ fleet, had somehow ended up on the Maledives, but had finally made it to Colombo. The troops had immediately been sent to Mannar, and from there had arrived at Jaffanapatnam. Van Goens’ army now counted 1100 soldiers. With this force, the southern side of the city was finally taken by the 18th of March. This however, still left the fortress in its centre to be conquered.

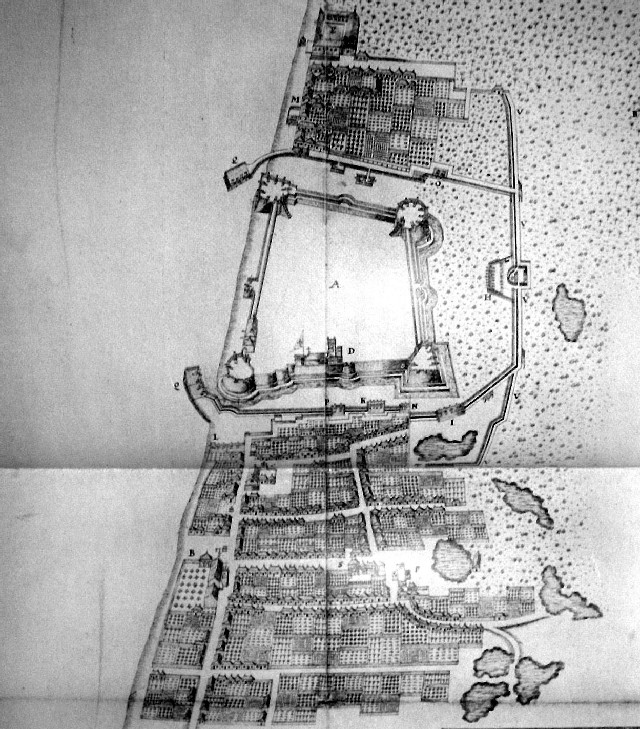

The fortress and city of Jaffanapatnam

Jaffanapatnam was one of the strongest fortresses the Portuguese possessed in Asia. It was larger than fortress Batavia, its walls were thick and 30 feet high, and the four corners were all excellent bastions. Climbing these walls or storming the fortress was unfeasible, Van Goens was somewhat low on gunpowder and did not wish to try and breach the walls by bombardment, so there was nothing for it but to begin building siege works and starve the city.[6] Trenches were dug, and under severe Portuguese fire from the fortress, the city was slowly sealed in. Various smaller ships had arrived from Mannar, which also sealed off the city from the sea. By the 30th of March, the siege works had closed in the fortress on all sides.

The Portuguese were also still in possession of a smaller fortress on an island called Kay just before Jaffanapatnam, which was a serious threat to both the ships and the Dutch positions around Jaffanapatnam. Before moving against Jaffanapatnam, Van Goens decided to first take this fortress. On the 19th of April, he bombarded Kay from the surrounding islands and ships. Although the bombardment was far from successful and the Portuguese subsequently refused to surrender, by a stroke of fortune the bombardment had destroyed the water supply inside the fortress. Just as Van Goens, as yet unaware of the destroyed water supply, was preparing to land at the small island and storm the fortress, which would have been a precarious undertaking, thirst made the Portuguese surrender the fortress on the 26th of April.

The siege of Jaffanapatnam, meanwhile, continued. The Portuguese inside the fortress had received the rumour that a Portuguese fleet would be arriving to break the siege, and held out. The Company forces had by now successfully sealed off the city. What the Company troops did not know was that before the arrival of the Company army, many civilians had fled inside the fortress from the city and the surrounding area. Almost 6000 people had been packed into the fortress, and resources were rapidly draining. Portuguese deserters informed Van Goens that an epidemic had also broken out. In the end, all Van Goens therefore had to do was wait it out.

On the 21st of June, a letter arrived from the fortress, requesting a ceasefire and negotiations. The next day, the city officially surrendered. 3500 survivors left the fortress; as many as 2170 people had died during the siege of the last three months. Jaffanapatnam had successfully been starved. The Company army only entered the fortress three days later, fearing the disease that had raged through it. The Portuguese who had survived the siege were either transported to Goa or to Batavia.[7]

With the fall of Jaffanapatnam, the Portuguese had entirely been driven from Ceylon. The cinnamon trade had now been monopolized. Securing this monopoly against possible future attack, however, would mean the end of several more Portuguese cities in India.